- SAP Community

- Products and Technology

- Technology

- Technology Blogs by Members

- Usage of Illicit Drugs in Australia.

Technology Blogs by Members

Explore a vibrant mix of technical expertise, industry insights, and tech buzz in member blogs covering SAP products, technology, and events. Get in the mix!

Turn on suggestions

Auto-suggest helps you quickly narrow down your search results by suggesting possible matches as you type.

Showing results for

Former Member

Options

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Mark as New

- Mark as Read

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Printer Friendly Page

- Report Inappropriate Content

10-13-2016

11:20 PM

Written by: Aditya singh negi 4560423 and Ranjot singh 4560421.

As post Graduate students studying at Victoria University, we are fortunate enough to work with influential mentors. One of them is our lecturer, Parvez Ahmad , who made us write this blog as part of our course assessment, and we must say that this is a challenging experience for us, because it is our first ever blog on any forum.

Definition of illicit drugs used.

Illicit use of a drug’ or ‘illicit drug use’ (used interchangeably in this report) can encompass a number of broad categories including illegal drugs, a drug that is prohibited from manufacture, sale or possession in Australia—for example cannabis, cocaine, heroin and amphetamine-type stimulants. Pharmaceuticals—a drug that is available from a pharmacy, over the counter or by prescription, which may be subject to misuse—for example opioid-based pain relief medications, opioid substitution therapies, benzodiazepines, over-the-counter codeine and steroids. Other psychoactive substances—legal or illegal, potentially used in a harmful way—for example kava, synthetic cannabis and other synthetic drugs, or inhalants such as petrol, paint or glue(Ritter, Lancaster, Grech, & Reuter, 2011) (MCDS 2011).

The decision to use drugs for the first time and to continue using them is influenced by a number of factors. Most people use drugs because they want to feel better or different. There are different categories of drug use including experimental use (try it once or twice out of curiosity), recreational use (for enjoyment, to enhance a mood or social occasion), situational use (cope with the demands of a situation) and dependent use (need it consistently to feel normal or avoid withdrawals) (ADF 2013). People may not be aware of the underlying reasons they take drugs or may answer in a way they deem to be more socially acceptable(Smart & Ogborne, 2000).

In 2013, of people aged 14 or older, the most common reason that an illicit substance was first used

Was curiosity (66%), followed by wanting to do something exciting (19.2%) and wanting to enhance an experience (13.3%). The majority of lifetime drug users said they no longer used illicit drugs (44%) or that they only tried illicit drugs once (30%). Among those who continued to use the drug, the most common reason for continuing drug use was because they wanted to enhance experiences (30%) or do something exciting (17.5%). About 1 in 10 said their friends influenced them or family (10.7%) or they took drugs to improve their mood or stop feeling unhappy (10.2%). Ex-users of illicit drugs were more likely to admit to being influenced by their friends and family than recent users (19.7% compared with 9.4%)(McMorris, Hemphill, Toumbourou, Catalano, & Patton, 2007).

Major factors that influence Illicit drugs usage

A System was born for Illicit Drug Reporting System (IDRS) was piloted in NSW in 1996 due to high accruing issues of drugs in each states of Australia. In the beginning of 2000 the system was well trained to identify the issues and how to tackle the problem(STRATEGY, 2004).

They conducted three types of Interviews.

- Interviews with Illicit Drug Users (Injectors)

- Interviews with key experts (Law and health Profession.

- Indicator data (Large Population Based Data Sets e.g. Arrests, Hospital overdoses.

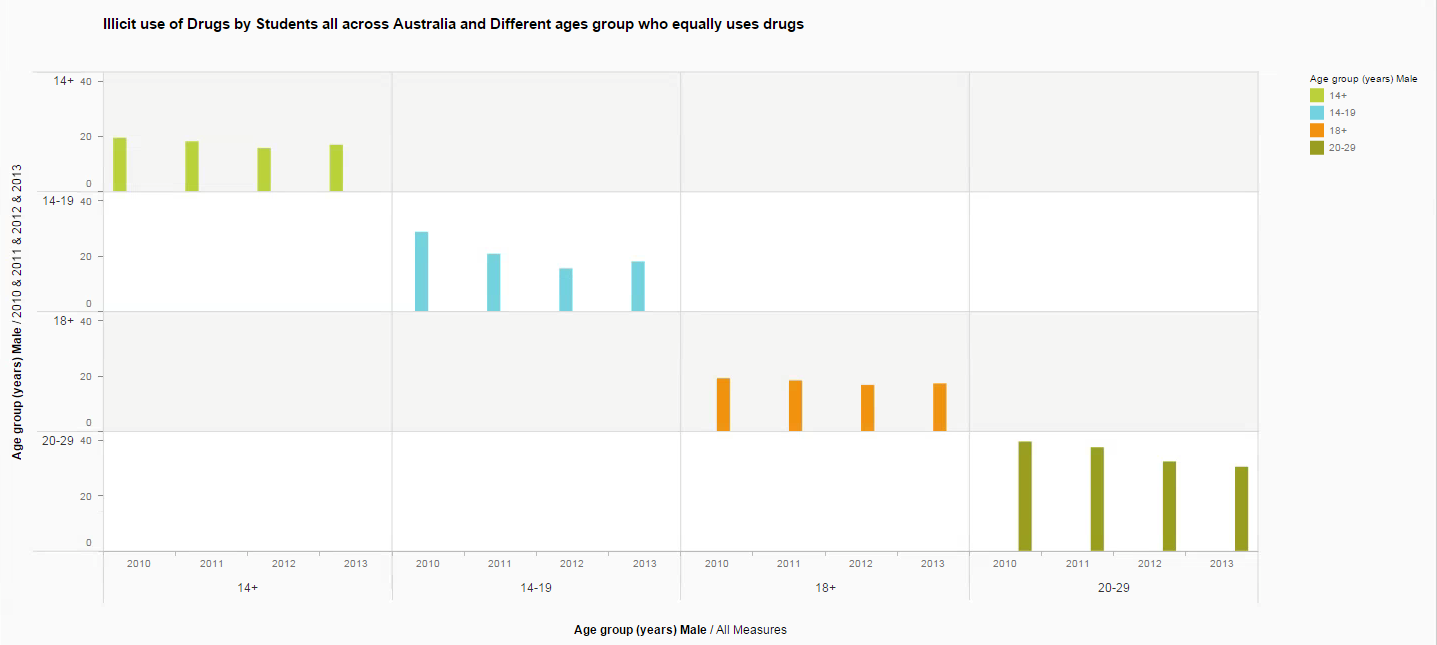

As per the information gathered from various sources it came to understand that relative standards errors of 25% to 50% includes designer drugs, which are used for non-medical purpose. As form the above chart we can identify the various age groups of students that are impacted with the drugs issues is between 14-30. That’s also including international students who travel to Australia for international studies(Handelsman & Gupta, 1997).

Pharmaceuticals are used for non-medical purposes

The above graph explains about what age group of students gets addicted to Illicit drugs as we can see that students starts using drugs at the early age of 14. Based on the surveyed report we found that ages group is not fixed it could vary between 14-30 years. Age that consumed high amount illicit drug are between 20-29 years, 89% heterosexual, 84% were unemployed student, 53% single students, 27% completed tertiary qualifications, 56% had a prison history in Australia and 47% were under drug treatment. It is observed that harms around injecting drug use including veins damages, dirty hits, thrombosis, bruising, abscesses and overdose. Illicit drug use has both short-term and long-term health effects, and health impacts can be severe, including poisoning, infective endocarditis (an infection that damages the heart valves), mental illness, self-harm, suicide and death. The use of inhalants may lead to brain damage, disability and death. The use of some illicit drugs by injection can also allow the transmission of blood borne viruses, including HIV/AIDS, hepatitis C and hepatitis B. The social impacts of illicit drug use include stressed family relationships, family breakdown, domestic violence, child abuse, assaults and crime (NRHA 2012).

Illicit usage of drugs by students

The most common drug used both recently and over the lifetime was cannabis, used by 10.2% and 35% respectively of people aged 14 and over(Donnelly & Hall, 1994). Among people aged 14–24, the age of initiation into illicit drug use rose from 16.0 in 2010 to 16.3 in 2013. More specifically, the age at which people first used cannabis and meth/amphetamines increased with both these drugs showing an older age of first use in 2013(Donnelly, Hall, & Christie, 1995). People aged 50 and over generally have the lowest rates of illicit drug use; however, in recent years this age group has shown the largest rise in illicit use of drugs and were the only age groups to show a statistically significant increase in use in 2013 (from 8.8% to 11.1% for those aged 50–59 and from 5.2 to6.4% for those aged 60 or older); this was mainly due to an increase in use of cannabis. In 2013, 1.2% of the population (or about 230,000 people) had used synthetic cannabinoids in the last 12 months, and 0.4% (or about 80,000 people) had used other emerging psychoactive substances such as mephedrone. Cannabis and meth/amphetamine users were more likely to use these drugs on a regular basis with most people using them at least every few months (64% and 52% respectively) while ecstasy and cocaine use was more likely to be infrequent, with many users only using the drug once or twice a year (54% and 71% respectively). While there was no rise in meth/amphetamine use in 2013, there was a change in the main form of meth/amphetamines used. Among meth/amphetamine users, use of powder fell from 51% in 2010 to 29% in 2013while the use of ice (also known as crystal) more than doubled, from 22% to 50% over the same period. More frequent use of the drug was also reported among meth/amphetamine users in 2013 with an increase in daily or weekly use (from 9.3% to 15.5%). Among ice users there was a doubling from 12.4% to 25%(Topp, Hando, Dillon, Roche, & Solowij, 1999).

Cannabis users in Australia region

There are a wide variety of strategies and services available to minimize the use and harm associated with cannabis use. In 2007, the National Cannabis Prevention and Information Centre was established to educate and train health professionals with the aim of increasing early intervention and reducing cannabis use(Hughes, 2012). In 2013, it was estimated that about 6.6 million (or 35%) people aged 14 or older had used cannabis in their lifetime and about 1.9 million (or 10.2%) had used cannabis in the previous 12 months. Around 1 in 5 (21%) people aged 14 or older had been offered or had the opportunity to use cannabis in the previous 12 months, and 1 in 10 (10.2%) reported that they did use cannabis in that time. About 1 in 20 Australians (5.3%) had used in the month prior to the survey and 3.5% had used in the previous week. More specifically: males were more likely to use cannabis at any frequency, than females. Among people aged 14–24, the age at which they first tried cannabis increased from 16.2 to 16.7 between 2010 and 2013. Cannabis users were more likely to try cannabis in their teens and age of first use was younger compared to other illicit drugs. Recent cannabis users (median age of 30 in 2013) were generally older than users of ecstasy (age 25), meth/amphetamines (age 28) and hallucinogens (age 24), one-third (32%) of recent cannabis users used the drug as often as weekly and older people (50 or older) were more likely than younger people to use cannabis regularly, with at least 4 in 10 recent users in these age groups using it as often as once a week or more, one-fifth (19.8%) of recent cannabis users stated that all or most of their friends currently used cannabis, in contrast to only 0.8% of those who had never used the drug(Roxburgh et al., 2010).

Illicit usage of drugs in rural & regional areas of Australia

In 2013, students who were addicted to illicit drugs were about 1.3 million (7.0%) people had used meth/amphetamines in their lifetime and 400,000 (2.1%) had done so in the last 12 months(Coffey, Lynskey, Wolfe, & Patton, 2000). Males were more likely than females to have used meth/amphetamines in their lifetime (8.6% and 5.3%, respectively) or in the last 12 months (2.7% and 1.5% respectively). In addition people aged 30–39 were slightly more likely than those in other age groups to have ever used meth/amphetamines (14.7%), while people aged 20–29 were more likely to have recently used meth/amphetamines (5.8%) meth/amphetamine users are getting older; the average age of users was 24 in 2001, compared with 28 in 2013 and age of first use was also older, increasing from 17.9 in 2010 to 18.6 in 2013 among young people aged 14–24 most people who were offered or had the opportunity to use meth/amphetamines didn’t use it—5.8% of people aged 14 or older were offered meth/amphetamines and 2.1% had used it among people aged 20–29, 14.1% had been offered or had the opportunity to use the drug, and 5.8% had used it(Macleod et al., 2004).

In 2013, students who were addicted to illicit drugs were about 1.3 million (7.0%) people had used meth/amphetamines in their lifetime and 400,000 (2.1%) had done so in the last 12 months(Coffey, Lynskey, Wolfe, & Patton, 2000). Males were more likely than females to have used meth/amphetamines in their lifetime (8.6% and 5.3%, respectively) or in the last 12 months (2.7% and 1.5% respectively). In addition people aged 30–39 were slightly more likely than those in other age groups to have ever used meth/amphetamines (14.7%), while people aged 20–29 were more likely to have recently used meth/amphetamines (5.8%) meth/amphetamine users are getting older; the average age of users was 24 in 2001, compared with 28 in 2013 and age of first use was also older, increasing from 17.9 in 2010 to 18.6 in 2013 among young people aged 14–24 most people who were offered or had the opportunity to use meth/amphetamines didn’t use it—5.8% of people aged 14 or older were offered meth/amphetamines and 2.1% had used it among people aged 20–29, 14.1% had been offered or had the opportunity to use the drug, and 5.8% had used it(Macleod et al., 2004).National drug strategy household survey detailed report 2013.

There are multiple and interrelated causes of illicit drug use in rural and regional Australia. Studies in rural Victoria and rural South Australia have identified distance and isolation for students as they feel, lack of public transport, lack of employment opportunities, uncertainty about the future and lack of leisure activities as contributing to illicit drug use in rural communities (NRHA 2012).

88 People in Remote and very remote areas were more likely to have used an illicit drug in the last 12 months than people in Major cities and Inner regional areas, but the type of drug used varied by remoteness area. For example:

- Cannabis was more commonly used by people in Outer regional (12.0%) and Remote and very remote areas (13.6%).

- People in Remote and very remote areas were twice as likely to have used meth/amphetamines as people in Major cities (4.4% compared with 2.1%).

- Ecstasy was more commonly used by people in Major cities (2.9%).

- Cocaine was more likely to be used by people in Major cities (2.6%) and Remote and very remote areas (2.5%) when compared with people in other remoteness areas.

Reference:

- Coffey, C., Lynskey, M., Wolfe, R., & Patton, G. 2000. Initiation and progression of cannabis use in a population‐based Australian adolescent longitudinal study. Addiction, 95(11): 1679-1690.

- Donnelly, N., & Hall, W. 1994. Patterns of cannabis use in Australia.

- Donnelly, N., Hall, W., & Christie, P. 1995. The effects of partial decriminalisation on cannabis use in South Australia, 1985 to 1993. Australian journal of public health, 19(3): 281-287.

- Handelsman, D., & Gupta, L. 1997. Prevalence and risk factors for anabolic‐androgenic steroid abuse in Australian high school students. International journal of andrology, 20(3): 159-164.

- Hughes, C. 2012. The Australian (illicit) drug policy timeline: 1985-2012. Drug Policy Modelling Program.

- Macleod, J., Oakes, R., Copello, A., Crome, I., Egger, M., Hickman, M., Oppenkowski, T., Stokes-Lampard, H., & Smith, G. D. 2004. Psychological and social sequelae of cannabis and other illicit drug use by young people: a systematic review of longitudinal, general population studies. The Lancet, 363(9421): 1579-1588.

- McMorris, B. J., Hemphill, S. A., Toumbourou, J. W., Catalano, R. F., & Patton, G. C. 2007. Prevalence of substance use and delinquent behavior in adolescents from Victoria, Australia and Washington State, United States. Health education & behavior, 34(4): 634-650.

- Ritter, A., Lancaster, K., Grech, K., & Reuter, P. 2011. An assessment of illicit drug policy in Australia (1985 to 2010): Themes and trends: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre.

- Roxburgh, A., Hall, W. D., Degenhardt, L., McLaren, J., Black, E., Copeland, J., & Mattick, R. P. 2010. The epidemiology of cannabis use and cannabis‐related harm in Australia 1993– Addiction, 105(6): 1071-1079.

- Smart, R. G., & Ogborne, A. C. 2000. Drug use and drinking among students in 36 countries. Addictive behaviors, 25(3): 455-460.

- STRATEGY, M. C. O. D. 2004. The prevention of substance use, risk and harm in Australia.

- Topp, L., Hando, J., Dillon, P., Roche, A., & Solowij, N. 1999. Ecstasy use in Australia: patterns of use and associated harm. Drug and alcohol dependence, 55(1): 105-115.

- SAP Managed Tags:

- SAP Lumira

You must be a registered user to add a comment. If you've already registered, sign in. Otherwise, register and sign in.

Labels in this area

-

"automatische backups"

1 -

"regelmäßige sicherung"

1 -

"TypeScript" "Development" "FeedBack"

1 -

505 Technology Updates 53

1 -

ABAP

14 -

ABAP API

1 -

ABAP CDS Views

2 -

ABAP CDS Views - BW Extraction

1 -

ABAP CDS Views - CDC (Change Data Capture)

1 -

ABAP class

2 -

ABAP Cloud

2 -

ABAP Development

5 -

ABAP in Eclipse

1 -

ABAP Platform Trial

1 -

ABAP Programming

2 -

abap technical

1 -

absl

2 -

access data from SAP Datasphere directly from Snowflake

1 -

Access data from SAP datasphere to Qliksense

1 -

Accrual

1 -

action

1 -

adapter modules

1 -

Addon

1 -

Adobe Document Services

1 -

ADS

1 -

ADS Config

1 -

ADS with ABAP

1 -

ADS with Java

1 -

ADT

2 -

Advance Shipping and Receiving

1 -

Advanced Event Mesh

3 -

AEM

1 -

AI

7 -

AI Launchpad

1 -

AI Projects

1 -

AIML

9 -

Alert in Sap analytical cloud

1 -

Amazon S3

1 -

Analytical Dataset

1 -

Analytical Model

1 -

Analytics

1 -

Analyze Workload Data

1 -

annotations

1 -

API

1 -

API and Integration

3 -

API Call

2 -

Application Architecture

1 -

Application Development

5 -

Application Development for SAP HANA Cloud

3 -

Applications and Business Processes (AP)

1 -

Artificial Intelligence

1 -

Artificial Intelligence (AI)

5 -

Artificial Intelligence (AI) 1 Business Trends 363 Business Trends 8 Digital Transformation with Cloud ERP (DT) 1 Event Information 462 Event Information 15 Expert Insights 114 Expert Insights 76 Life at SAP 418 Life at SAP 1 Product Updates 4

1 -

Artificial Intelligence (AI) blockchain Data & Analytics

1 -

Artificial Intelligence (AI) blockchain Data & Analytics Intelligent Enterprise

1 -

Artificial Intelligence (AI) blockchain Data & Analytics Intelligent Enterprise Oil Gas IoT Exploration Production

1 -

Artificial Intelligence (AI) blockchain Data & Analytics Intelligent Enterprise sustainability responsibility esg social compliance cybersecurity risk

1 -

ASE

1 -

ASR

2 -

ASUG

1 -

Attachments

1 -

Authorisations

1 -

Automating Processes

1 -

Automation

2 -

aws

2 -

Azure

1 -

Azure AI Studio

1 -

B2B Integration

1 -

Backorder Processing

1 -

Backup

1 -

Backup and Recovery

1 -

Backup schedule

1 -

BADI_MATERIAL_CHECK error message

1 -

Bank

1 -

BAS

1 -

basis

2 -

Basis Monitoring & Tcodes with Key notes

2 -

Batch Management

1 -

BDC

1 -

Best Practice

1 -

bitcoin

1 -

Blockchain

3 -

bodl

1 -

BOP in aATP

1 -

BOP Segments

1 -

BOP Strategies

1 -

BOP Variant

1 -

BPC

1 -

BPC LIVE

1 -

BTP

12 -

BTP Destination

2 -

Business AI

1 -

Business and IT Integration

1 -

Business application stu

1 -

Business Application Studio

1 -

Business Architecture

1 -

Business Communication Services

1 -

Business Continuity

1 -

Business Data Fabric

3 -

Business Partner

12 -

Business Partner Master Data

10 -

Business Technology Platform

2 -

Business Trends

4 -

CA

1 -

calculation view

1 -

CAP

3 -

Capgemini

1 -

CAPM

1 -

Catalyst for Efficiency: Revolutionizing SAP Integration Suite with Artificial Intelligence (AI) and

1 -

CCMS

2 -

CDQ

12 -

CDS

2 -

Cental Finance

1 -

Certificates

1 -

CFL

1 -

Change Management

1 -

chatbot

1 -

chatgpt

3 -

CL_SALV_TABLE

2 -

Class Runner

1 -

Classrunner

1 -

Cloud ALM Monitoring

1 -

Cloud ALM Operations

1 -

cloud connector

1 -

Cloud Extensibility

1 -

Cloud Foundry

4 -

Cloud Integration

6 -

Cloud Platform Integration

2 -

cloudalm

1 -

communication

1 -

Compensation Information Management

1 -

Compensation Management

1 -

Compliance

1 -

Compound Employee API

1 -

Configuration

1 -

Connectors

1 -

Consolidation Extension for SAP Analytics Cloud

2 -

Control Indicators.

1 -

Controller-Service-Repository pattern

1 -

Conversion

1 -

Cosine similarity

1 -

cryptocurrency

1 -

CSI

1 -

ctms

1 -

Custom chatbot

3 -

Custom Destination Service

1 -

custom fields

1 -

Customer Experience

1 -

Customer Journey

1 -

Customizing

1 -

cyber security

3 -

cybersecurity

1 -

Data

1 -

Data & Analytics

1 -

Data Aging

1 -

Data Analytics

2 -

Data and Analytics (DA)

1 -

Data Archiving

1 -

Data Back-up

1 -

Data Flow

1 -

Data Governance

5 -

Data Integration

2 -

Data Quality

12 -

Data Quality Management

12 -

Data Synchronization

1 -

data transfer

1 -

Data Unleashed

1 -

Data Value

8 -

database tables

1 -

Datasphere

3 -

datenbanksicherung

1 -

dba cockpit

1 -

dbacockpit

1 -

Debugging

2 -

Delimiting Pay Components

1 -

Delta Integrations

1 -

Destination

3 -

Destination Service

1 -

Developer extensibility

1 -

Developing with SAP Integration Suite

1 -

Devops

1 -

digital transformation

1 -

Documentation

1 -

Dot Product

1 -

DQM

1 -

dump database

1 -

dump transaction

1 -

e-Invoice

1 -

E4H Conversion

1 -

Eclipse ADT ABAP Development Tools

2 -

edoc

1 -

edocument

1 -

ELA

1 -

Embedded Consolidation

1 -

Embedding

1 -

Embeddings

1 -

Employee Central

1 -

Employee Central Payroll

1 -

Employee Central Time Off

1 -

Employee Information

1 -

Employee Rehires

1 -

Enable Now

1 -

Enable now manager

1 -

endpoint

1 -

Enhancement Request

1 -

Enterprise Architecture

1 -

ETL Business Analytics with SAP Signavio

1 -

Euclidean distance

1 -

Event Dates

1 -

Event Driven Architecture

1 -

Event Mesh

2 -

Event Reason

1 -

EventBasedIntegration

1 -

EWM

1 -

EWM Outbound configuration

1 -

EWM-TM-Integration

1 -

Existing Event Changes

1 -

Expand

1 -

Expert

2 -

Expert Insights

2 -

Exploits

1 -

Fiori

14 -

Fiori Elements

2 -

Fiori SAPUI5

12 -

Flask

1 -

Full Stack

8 -

Funds Management

1 -

General

1 -

General Splitter

1 -

Generative AI

1 -

Getting Started

1 -

GitHub

8 -

Grants Management

1 -

GraphQL

1 -

groovy

1 -

GTP

1 -

HANA

6 -

HANA Cloud

2 -

Hana Cloud Database Integration

2 -

HANA DB

2 -

HANA XS Advanced

1 -

Historical Events

1 -

home labs

1 -

HowTo

1 -

HR Data Management

1 -

html5

8 -

HTML5 Application

1 -

Identity cards validation

1 -

idm

1 -

Implementation

1 -

input parameter

1 -

instant payments

1 -

Integration

3 -

Integration Advisor

1 -

Integration Architecture

1 -

Integration Center

1 -

Integration Suite

1 -

intelligent enterprise

1 -

iot

1 -

Java

1 -

job

1 -

Job Information Changes

1 -

Job-Related Events

1 -

Job_Event_Information

1 -

joule

4 -

Journal Entries

1 -

Just Ask

1 -

Kerberos for ABAP

8 -

Kerberos for JAVA

8 -

KNN

1 -

Launch Wizard

1 -

Learning Content

2 -

Life at SAP

5 -

lightning

1 -

Linear Regression SAP HANA Cloud

1 -

Loading Indicator

1 -

local tax regulations

1 -

LP

1 -

Machine Learning

2 -

Marketing

1 -

Master Data

3 -

Master Data Management

14 -

Maxdb

2 -

MDG

1 -

MDGM

1 -

MDM

1 -

Message box.

1 -

Messages on RF Device

1 -

Microservices Architecture

1 -

Microsoft Universal Print

1 -

Middleware Solutions

1 -

Migration

5 -

ML Model Development

1 -

Modeling in SAP HANA Cloud

8 -

Monitoring

3 -

MTA

1 -

Multi-Record Scenarios

1 -

Multiple Event Triggers

1 -

Myself Transformation

1 -

Neo

1 -

New Event Creation

1 -

New Feature

1 -

Newcomer

1 -

NodeJS

2 -

ODATA

2 -

OData APIs

1 -

odatav2

1 -

ODATAV4

1 -

ODBC

1 -

ODBC Connection

1 -

Onpremise

1 -

open source

2 -

OpenAI API

1 -

Oracle

1 -

PaPM

1 -

PaPM Dynamic Data Copy through Writer function

1 -

PaPM Remote Call

1 -

PAS-C01

1 -

Pay Component Management

1 -

PGP

1 -

Pickle

1 -

PLANNING ARCHITECTURE

1 -

Popup in Sap analytical cloud

1 -

PostgrSQL

1 -

POSTMAN

1 -

Process Automation

2 -

Product Updates

4 -

PSM

1 -

Public Cloud

1 -

Python

4 -

Qlik

1 -

Qualtrics

1 -

RAP

3 -

RAP BO

2 -

Record Deletion

1 -

Recovery

1 -

recurring payments

1 -

redeply

1 -

Release

1 -

Remote Consumption Model

1 -

Replication Flows

1 -

research

1 -

Resilience

1 -

REST

1 -

REST API

2 -

Retagging Required

1 -

Risk

1 -

Rolling Kernel Switch

1 -

route

1 -

rules

1 -

S4 HANA

1 -

S4 HANA Cloud

1 -

S4 HANA On-Premise

1 -

S4HANA

3 -

S4HANA_OP_2023

2 -

SAC

10 -

SAC PLANNING

9 -

SAP

4 -

SAP ABAP

1 -

SAP Advanced Event Mesh

1 -

SAP AI Core

8 -

SAP AI Launchpad

8 -

SAP Analytic Cloud Compass

1 -

Sap Analytical Cloud

1 -

SAP Analytics Cloud

4 -

SAP Analytics Cloud for Consolidation

3 -

SAP Analytics Cloud Story

1 -

SAP analytics clouds

1 -

SAP BAS

1 -

SAP Basis

6 -

SAP BODS

1 -

SAP BODS certification.

1 -

SAP BTP

21 -

SAP BTP Build Work Zone

2 -

SAP BTP Cloud Foundry

6 -

SAP BTP Costing

1 -

SAP BTP CTMS

1 -

SAP BTP Innovation

1 -

SAP BTP Migration Tool

1 -

SAP BTP SDK IOS

1 -

SAP Build

11 -

SAP Build App

1 -

SAP Build apps

1 -

SAP Build CodeJam

1 -

SAP Build Process Automation

3 -

SAP Build work zone

10 -

SAP Business Objects Platform

1 -

SAP Business Technology

2 -

SAP Business Technology Platform (XP)

1 -

sap bw

1 -

SAP CAP

2 -

SAP CDC

1 -

SAP CDP

1 -

SAP CDS VIEW

1 -

SAP Certification

1 -

SAP Cloud ALM

4 -

SAP Cloud Application Programming Model

1 -

SAP Cloud Integration for Data Services

1 -

SAP cloud platform

8 -

SAP Companion

1 -

SAP CPI

3 -

SAP CPI (Cloud Platform Integration)

2 -

SAP CPI Discover tab

1 -

sap credential store

1 -

SAP Customer Data Cloud

1 -

SAP Customer Data Platform

1 -

SAP Data Intelligence

1 -

SAP Data Migration in Retail Industry

1 -

SAP Data Services

1 -

SAP DATABASE

1 -

SAP Dataspher to Non SAP BI tools

1 -

SAP Datasphere

9 -

SAP DRC

1 -

SAP EWM

1 -

SAP Fiori

3 -

SAP Fiori App Embedding

1 -

Sap Fiori Extension Project Using BAS

1 -

SAP GRC

1 -

SAP HANA

1 -

SAP HCM (Human Capital Management)

1 -

SAP HR Solutions

1 -

SAP IDM

1 -

SAP Integration Suite

9 -

SAP Integrations

4 -

SAP iRPA

2 -

SAP LAGGING AND SLOW

1 -

SAP Learning Class

1 -

SAP Learning Hub

1 -

SAP Master Data

1 -

SAP Odata

2 -

SAP on Azure

1 -

SAP PartnerEdge

1 -

sap partners

1 -

SAP Password Reset

1 -

SAP PO Migration

1 -

SAP Prepackaged Content

1 -

SAP Process Automation

2 -

SAP Process Integration

2 -

SAP Process Orchestration

1 -

SAP S4HANA

2 -

SAP S4HANA Cloud

1 -

SAP S4HANA Cloud for Finance

1 -

SAP S4HANA Cloud private edition

1 -

SAP Sandbox

1 -

SAP STMS

1 -

SAP successfactors

3 -

SAP SuccessFactors HXM Core

1 -

SAP Time

1 -

SAP TM

2 -

SAP Trading Partner Management

1 -

SAP UI5

1 -

SAP Upgrade

1 -

SAP Utilities

1 -

SAP-GUI

8 -

SAP_COM_0276

1 -

SAPBTP

1 -

SAPCPI

1 -

SAPEWM

1 -

sapmentors

1 -

saponaws

2 -

SAPS4HANA

1 -

SAPUI5

5 -

schedule

1 -

Script Operator

1 -

Secure Login Client Setup

8 -

security

9 -

Selenium Testing

1 -

Self Transformation

1 -

Self-Transformation

1 -

SEN

1 -

SEN Manager

1 -

service

1 -

SET_CELL_TYPE

1 -

SET_CELL_TYPE_COLUMN

1 -

SFTP scenario

2 -

Simplex

1 -

Single Sign On

8 -

Singlesource

1 -

SKLearn

1 -

Slow loading

1 -

soap

1 -

Software Development

1 -

SOLMAN

1 -

solman 7.2

2 -

Solution Manager

3 -

sp_dumpdb

1 -

sp_dumptrans

1 -

SQL

1 -

sql script

1 -

SSL

8 -

SSO

8 -

Substring function

1 -

SuccessFactors

1 -

SuccessFactors Platform

1 -

SuccessFactors Time Tracking

1 -

Sybase

1 -

system copy method

1 -

System owner

1 -

Table splitting

1 -

Tax Integration

1 -

Technical article

1 -

Technical articles

1 -

Technology Updates

14 -

Technology Updates

1 -

Technology_Updates

1 -

terraform

1 -

Threats

2 -

Time Collectors

1 -

Time Off

2 -

Time Sheet

1 -

Time Sheet SAP SuccessFactors Time Tracking

1 -

Tips and tricks

2 -

toggle button

1 -

Tools

1 -

Trainings & Certifications

1 -

Transformation Flow

1 -

Transport in SAP BODS

1 -

Transport Management

1 -

TypeScript

2 -

ui designer

1 -

unbind

1 -

Unified Customer Profile

1 -

UPB

1 -

Use of Parameters for Data Copy in PaPM

1 -

User Unlock

1 -

VA02

1 -

Validations

1 -

Vector Database

2 -

Vector Engine

1 -

Visual Studio Code

1 -

VSCode

1 -

Vulnerabilities

1 -

Web SDK

1 -

work zone

1 -

workload

1 -

xsa

1 -

XSA Refresh

1

- « Previous

- Next »

Related Content

- SAUG Conference Brisbane 2023 in Technology Blogs by Members

- I can see ABAP Moon Rising – Part Seven of Eight in Technology Blogs by Members

- GRC Tuesdays: As Transaction Laundering Expands, SAP Offers Sophisticated Screening Tools in Technology Blogs by SAP

- A brief overview of the refugee issue in Australia in Technology Blogs by Members

Top kudoed authors

| User | Count |

|---|---|

| 8 | |

| 5 | |

| 5 | |

| 4 | |

| 4 | |

| 4 | |

| 4 | |

| 4 | |

| 3 | |

| 3 |